Knowing What Has Gone on and Is Going on Around You in Society Is Called

An information guild is a guild where the usage, creation, distribution, manipulation and integration of information is a significant activeness.[1] Its primary drivers are information and communication technologies, which accept resulted in rapid data growth in diversity and is somehow changing all aspects of social organization, including pedagogy, economy,[2] health, government,[3] warfare, and levels of commonwealth.[4] The people who are able to partake in this form of society are sometimes called either computer users or even digital citizens, defined past Grand. Mossberger equally "Those who use the Internet regularly and finer". This is 1 of many dozen internet terms that have been identified to propose that humans are inbound a new and different stage of social club.[5]

Some of the markers of this steady change may be technological, economical, occupational, spatial, cultural, or a combination of all of these.[half dozen] Information lodge is seen as a successor to industrial society. Closely related concepts are the post-industrial society (post-fordism), post-modern guild, calculator lodge and cognition society, telematic society, guild of the spectacle (postmodernism), Information Revolution and Information Age, network society (Manuel Castells) or even liquid modernity.

Definition [edit]

There is currently no universally accepted concept of what exactly tin can be defined as an information society and what shall not be included in the term. Most theoreticians agree that a transformation tin can be seen equally started somewhere between the 1970s, the early on 1990s transformations of the Socialist East and the 2000s period that formed well-nigh of today's net principles and currently as is changing the way societies piece of work fundamentally. It goes beyond the internet, as the principles of internet pattern and usage influence other areas, and in that location are discussions about how large the influence of specific media or specific modes of product really is. Frank Webster notes five major types of information that can be used to define information club: technological, economic, occupational, spatial and cultural.[6] According to Webster, the graphic symbol of information has transformed the manner that we live today. How nosotros deport ourselves centers around theoretical knowledge and information.[vii]

Kasiwulaya and Gomo (Makerere Academy) insinuate[ where? ] [ dubious ] that data societies are those that have intensified their use of IT for economic, social, cultural and political transformation. In 2005, governments reaffirmed their dedication to the foundations of the Information Social club in the Tunis Commitment and outlined the footing for implementation and follow-up in the Tunis Agenda for the Data Guild. In item, the Tunis Agenda addresses the issues of financing of ICTs for evolution and Internet governance that could not be resolved in the first phase.

Some people, such every bit Antonio Negri, characterize the information society equally ane in which people practise immaterial labour.[8] By this, they announced to refer to the production of knowledge or cultural artifacts. One problem with this model is that it ignores the material and essentially industrial basis of the society. However it does point to a trouble for workers, namely how many creative people does this society need to role? For example, information technology may be that you only demand a few star performers, rather than a plethora of non-celebrities, as the piece of work of those performers can be easily distributed, forcing all secondary players to the lesser of the market. It is now mutual for publishers to promote only their best selling authors and to attempt to avoid the residuum—fifty-fifty if they still sell steadily. Films are becoming more and more than judged, in terms of distribution, past their first weekend's performance, in many cases cut out opportunity for give-and-take-of-mouth development.

Michael Buckland characterizes data in society in his book Data and Club. Buckland expresses the idea that information tin can be interpreted differently from person to person based on that individual's experiences.[9]

Considering that metaphors and technologies of information move forward in a reciprocal relationship, we can describe some societies (especially the Japanese order) as an information social club because we think of it as such.[ten] [11]

The word information may be interpreted in many different ways. According to Buckland in Information and Order, nearly of the meanings fall into three categories of human cognition: data every bit knowledge, information equally a process, and information as a affair.[12]

The growth of reckoner information in guild [edit]

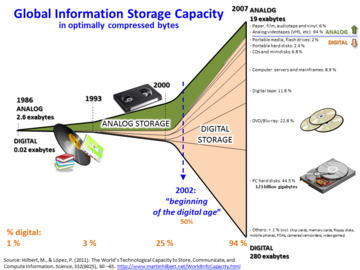

The amount of data stored globally has increased greatly since the 1980s, and by 2007, 94% of it was stored digitally. Source

The growth of the amount of technologically mediated information has been quantified in different ways, including gild'southward technological chapters to shop information, to communicate information, and to compute information.[15] It is estimated that, the world's technological capacity to store information grew from ii.6 (optimally compressed) exabytes in 1986, which is the informational equivalent to less than one 730-MB CD-ROM per person in 1986 (539 MB per person), to 295 (optimally compressed) exabytes in 2007.[xvi] This is the informational equivalent of lx CD-ROM per person in 2007[17] and represents a sustained almanac growth charge per unit of some 25%. The world'due south combined technological chapters to receive information through one-mode broadcast networks was the informational equivalent of 174 newspapers per person per mean solar day in 2007.[16]

The globe's combined effective capacity to substitution data through two-way telecommunications networks was 281 petabytes of (optimally compressed) information in 1986, 471 petabytes in 1993, two.ii (optimally compressed) exabytes in 2000, and 65 (optimally compressed) exabytes in 2007, which is the informational equivalent of 6 newspapers per person per day in 2007.[17] The world's technological capacity to compute information with humanly guided general-purpose computers grew from 3.0 × ten^8 MIPS in 1986, to 6.four x 10^12 MIPS in 2007, experiencing the fastest growth rate of over 60% per twelvemonth during the last two decades.[xvi]

James R. Beniger describes the necessity of data in modern club in the following way: "The need for sharply increased control that resulted from the industrialization of material processes through awarding of inanimate sources of energy probably accounts for the rapid development of automatic feedback technology in the early industrial period (1740-1830)" (p. 174) "Even with enhanced feedback control, industry could not have developed without the enhanced ways to process matter and energy, not only as inputs of the raw materials of product but too every bit outputs distributed to concluding consumption."(p. 175)[5]

Development of the information order model [edit]

One of the first people to develop the concept of the information society was the economist Fritz Machlup. In 1933, Fritz Machlup began studying the event of patents on research. His piece of work culminated in the written report The product and distribution of knowledge in the United States in 1962. This volume was widely regarded[18] and was eventually translated into Russian and Japanese. The Japanese accept likewise studied the information society (or jōhōka shakai, 情報化社会).

The issue of technologies and their role in gimmicky social club have been discussed in the scientific literature using a range of labels and concepts. This section introduces some of them. Ideas of a knowledge or data economic system, post-industrial society, postmodern order, network club, the information revolution, informational capitalism, network capitalism, and the like, take been debated over the concluding several decades.

Fritz Machlup (1962) introduced the concept of the cognition industry. He began studying the furnishings of patents on research before distinguishing five sectors of the knowledge sector: educational activity, research and development, mass media, information technologies, data services. Based on this categorization he calculated that in 1959 29% per cent of the GNP in the USA had been produced in knowledge industries.[19] [20] [ citation needed ]

Economic transition [edit]

Peter Drucker has argued that there is a transition from an economy based on textile appurtenances to one based on knowledge.[21] Marc Porat distinguishes a primary (information goods and services that are directly used in the production, distribution or processing of information) and a secondary sector (information services produced for internal consumption past government and non-information firms) of the data economy.[22]

Porat uses the total value added past the chief and secondary data sector to the GNP as an indicator for the data economy. The OECD has employed Porat's definition for computing the share of the information economy in the total economic system (eastward.g. OECD 1981, 1986). Based on such indicators, the data social club has been defined as a society where more than than half of the GNP is produced and more than one-half of the employees are active in the information economy.[23]

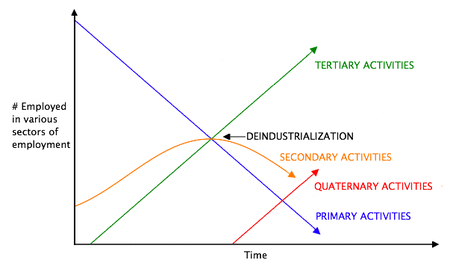

For Daniel Bong the number of employees producing services and information is an indicator for the advisory character of a guild. "A postal service-industrial society is based on services. (…) What counts is not raw muscle power, or energy, only information. (…) A postal service industrial guild is one in which the majority of those employed are not involved in the production of tangible appurtenances".[24]

Alain Touraine already spoke in 1971 of the mail-industrial social club. "The passage to postindustrial guild takes place when investment results in the production of symbolic goods that modify values, needs, representations, far more than than in the production of material goods or even of 'services'. Industrial society had transformed the means of production: post-industrial lodge changes the ends of production, that is, culture. (…) The decisive bespeak here is that in postindustrial society all of the economic system is the object of intervention of social club upon itself. That is why we tin call it the programmed society, because this phrase captures its chapters to create models of direction, product, organisation, distribution, and consumption, so that such a society appears, at all its functional levels, as the product of an activeness exercised by the society itself, and not as the outcome of natural laws or cultural specificities" (Touraine 1988: 104). In the programmed society too the area of cultural reproduction including aspects such as information, consumption, health, enquiry, educational activity would be industrialized. That modern society is increasing its capacity to act upon itself means for Touraine that society is reinvesting always larger parts of production and then produces and transforms itself. This makes Touraine's concept essentially different from that of Daniel Bell who focused on the capacity to procedure and generate data for efficient society operation.

Jean-François Lyotard[25] has argued that "noesis has become the principle [sic] forcefulness of production over the concluding few decades". Knowledge would exist transformed into a article. Lyotard says that postindustrial lodge makes knowledge accessible to the layman considering cognition and information technologies would diffuse into society and intermission up M Narratives of centralized structures and groups. Lyotard denotes these changing circumstances as postmodern status or postmodern order.

Similarly to Bong, Peter Otto and Philipp Sonntag (1985) say that an information society is a society where the majority of employees piece of work in data jobs, i.e. they have to deal more than with information, signals, symbols, and images than with energy and affair. Radovan Richta (1977) argues that society has been transformed into a scientific civilization based on services, teaching, and creative activities. This transformation would exist the consequence of a scientific-technological transformation based on technological progress and the increasing importance of computer technology. Scientific discipline and engineering would get immediate forces of product (Aristovnik 2014: 55).

Nico Stehr (1994, 2002a, b) says that in the knowledge gild a bulk of jobs involves working with knowledge. "Contemporary society may be described equally a knowledge society based on the all-encompassing penetration of all its spheres of life and institutions by scientific and technological noesis" (Stehr 2002b: 18). For Stehr, cognition is a capacity for social action. Science would become an immediate productive force, knowledge would no longer be primarily embodied in machines, but already appropriated nature that represents noesis would be rearranged according to certain designs and programs (Ibid.: 41-46). For Stehr, the economic system of a knowledge society is largely driven not by material inputs, but by symbolic or cognition-based inputs (Ibid.: 67), there would be a large number of professions that involve working with noesis, and a failing number of jobs that demand low cognitive skills as well as in manufacturing (Stehr 2002a).

Also Alvin Toffler argues that knowledge is the central resource in the economy of the information order: "In a Tertiary Wave economy, the central resource – a unmarried word broadly encompassing data, information, images, symbols, culture, credo, and values – is actionable cognition" (Dyson/Gilder/Keyworth/Toffler 1994).

At the end of the twentieth century, the concept of the network society gained importance in information society theory. For Manuel Castells, network logic is besides data, pervasiveness, flexibility, and convergence a central feature of the data engineering paradigm (2000a: 69ff). "One of the central features of informational social club is the networking logic of its basic structure, which explains the use of the concept of 'network society'" (Castells 2000: 21). "As an historical trend, ascendant functions and processes in the Information Historic period are increasingly organized around networks. Networks constitute the new social morphology of our societies, and the diffusion of networking logic essentially modifies the operation and outcomes in processes of production, feel, power, and civilization" (Castells 2000: 500). For Castells the network social club is the upshot of informationalism, a new technological paradigm.

Jan Van Dijk (2006) defines the network society every bit a "social formation with an infrastructure of social and media networks enabling its prime mode of organization at all levels (private, group/organizational and societal). Increasingly, these networks link all units or parts of this formation (individuals, groups and organizations)" (Van Dijk 2006: xx). For Van Dijk networks have become the nervous arrangement of society, whereas Castells links the concept of the network society to capitalist transformation, Van Dijk sees it equally the logical consequence of the increasing widening and thickening of networks in nature and order. Darin Barney uses the term for characterizing societies that exhibit two fundamental characteristics: "The first is the presence in those societies of sophisticated – most exclusively digital – technologies of networked communication and information management/distribution, technologies which form the basic infrastructure mediating an increasing assortment of social, political and economical practices. (…) The second, arguably more intriguing, characteristic of network societies is the reproduction and institutionalization throughout (and between) those societies of networks as the basic grade of human being organization and relationship across a wide range of social, political and economic configurations and associations".[26]

Critiques [edit]

The major critique of concepts such as information club, postmodern order, knowledge society, network gild, postindustrial social club, etc. that has mainly been voiced past critical scholars is that they create the impression that nosotros have entered a completely new type of social club. "If at that place is but more information then it is hard to understand why anyone should suggest that nosotros take before the states something radically new" (Webster 2002a: 259). Critics such every bit Frank Webster argue that these approaches stress discontinuity, as if gimmicky society had zilch in common with order as it was 100 or 150 years ago. Such assumptions would have ideological graphic symbol because they would fit with the view that we can practice nada nigh modify and have to adapt to existing political realities (kasiwulaya 2002b: 267).

These critics debate that gimmicky lodge first of all is withal a capitalist guild oriented towards accumulating economic, political, and cultural capital. They acknowledge that information society theories stress some important new qualities of society (notably globalization and informatization), simply charge that they fail to bear witness that these are attributes of overall backer structures. Critics such as Webster insist on the continuities that characterise change. In this manner Webster distinguishes between different epochs of capitalism: laissez-faire capitalism of the 19th century, corporate capitalism in the 20th century, and informational commercialism for the 21st century (kasiwulaya 2006).

For describing contemporary society based on a new dialectic of continuity and discontinuity, other disquisitional scholars take suggested several terms similar:

- transnational network commercialism, transnational informational capitalism (Christian Fuchs 2008, 2007): "Computer networks are the technological foundation that has allowed the emergence of global network capitalism, that is, regimes of accumulation, regulation, and discipline that are helping to increasingly base of operations the aggregating of economic, political, and cultural majuscule on transnational network organizations that make utilise of cyberspace and other new technologies for global coordination and communication. [...] The need to notice new strategies for executing corporate and political domination has resulted in a restructuration of capitalism that is characterized past the emergence of transnational, networked spaces in the economic, political, and cultural system and has been mediated past cyberspace as a tool of global coordination and advice. Economic, political, and cultural space have been restructured; they accept become more fluid and dynamic, have enlarged their borders to a transnational calibration, and handle the inclusion and exclusion of nodes in flexible ways. These networks are complex due to the loftier number of nodes (individuals, enterprises, teams, political actors, etc.) that can be involved and the high speed at which a high number of resource is produced and transported inside them. Just global network capitalism is based on structural inequalities; it is fabricated up of segmented spaces in which cardinal hubs (transnational corporations, certain political actors, regions, countries, Western lifestyles, and worldviews) centralize the production, control, and flows of economic, political, and cultural capital (belongings, power, definition capacities). This segmentation is an expression of the overall competitive character of gimmicky society." (Fuchs 2008: 110+119).

- digital commercialism (Schiller 2000, cf. as well Peter Glotz):[27] "networks are directly generalizing the social and cultural range of the capitalist economic system equally never before" (Schiller 2000: xiv)

- virtual capitalism: the "combination of marketing and the new information technology volition enable sure firms to obtain higher profit margins and larger market shares, and volition thereby promote greater concentration and centralization of upper-case letter" (Dawson/John Bellamy Foster 1998: 63sq),

- high-tech capitalism[28] or informatic capitalism (Fitzpatrick 2002) – to focus on the reckoner equally a guiding technology that has transformed the productive forces of capitalism and has enabled a globalized economy.

Other scholars adopt to speak of information capitalism (Morris-Suzuki 1997) or advisory commercialism (Manuel Castells 2000, Christian Fuchs 2005, Schmiede 2006a, b). Manuel Castells sees informationalism every bit a new technological paradigm (he speaks of a mode of development) characterized by "data generation, processing, and transmission" that have get "the primal sources of productivity and ability" (Castells 2000: 21). The "most decisive historical factor accelerating, channelling and shaping the information technology prototype, and inducing its associated social forms, was/is the procedure of backer restructuring undertaken since the 1980s, and so that the new techno-economical arrangement can be fairly characterized as informational commercialism" (Castells 2000: 18). Castells has added to theories of the information club the thought that in contemporary society ascendant functions and processes are increasingly organized around networks that constitute the new social morphology of society (Castells 2000: 500). Nicholas Garnham[29] is critical of Castells and argues that the latter'southward account is technologically determinist considering Castells points out that his approach is based on a dialectic of technology and society in which engineering science embodies society and order uses engineering science (Castells 2000: 5sqq). Simply Castells also makes clear that the rise of a new "mode of development" is shaped by capitalist production, i.e. by gild, which implies that technology isn't the simply driving strength of order.

Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt argue that contemporary order is an Empire that is characterized by a singular global logic of capitalist domination that is based on immaterial labour. With the concept of immaterial labour Negri and Hardt introduce ideas of information lodge discourse into their Marxist business relationship of gimmicky capitalism. Immaterial labour would be labour "that creates immaterial products, such as knowledge, information, advice, a relationship, or an emotional response" (Hardt/Negri 2005: 108; cf. also 2000: 280-303), or services, cultural products, knowledge (Hardt/Negri 2000: 290). There would be two forms: intellectual labour that produces ideas, symbols, codes, texts, linguistic figures, images, etc.; and melancholia labour that produces and manipulates affects such equally a feeling of ease, well-being, satisfaction, excitement, passion, joy, sadness, etc. (Ibid.).

Overall, neo-Marxist accounts of the information society have in common that they stress that knowledge, information technologies, and computer networks accept played a role in the restructuration and globalization of commercialism and the emergence of a flexible regime of accumulation (David Harvey 1989). They warn that new technologies are embedded into societal antagonisms that cause structural unemployment, rising poverty, social exclusion, the deregulation of the welfare state and of labour rights, the lowering of wages, welfare, etc.

Concepts such as noesis society, information society, network social club, informational capitalism, postindustrial society, transnational network capitalism, postmodern society, etc. show that there is a vivid discussion in gimmicky sociology on the character of contemporary social club and the role that technologies, data, communication, and co-operation play in it.[ commendation needed ] Information society theory discusses the role of information and information technology in society, the question which key concepts shall exist used for characterizing contemporary order, and how to define such concepts. It has become a specific branch of contemporary sociology.

Second and third nature [edit]

Information gild is the means of sending and receiving information from one identify to another.[30] As technology has advanced so likewise has the way people have adapted in sharing information with each other.

"Second nature" refers a group of experiences that get made over past culture.[31] They then go remade into something else that can then take on a new significant. As a society we transform this procedure and then it becomes something natural to us, i.e. 2nd nature. So, by following a particular pattern created by culture we are able to recognise how we use and move information in different ways. From sharing information via unlike time zones (such as talking online) to information ending up in a unlike location (sending a letter overseas) this has all become a habitual process that we as a society take for granted.[32]

However, through the process of sharing information vectors have enabled us to spread information fifty-fifty farther. Through the use of these vectors information is able to move and so split up from the initial things that enabled them to motion.[33] From here, something called "tertiary nature" has developed. An extension of second nature, 3rd nature is in control of 2nd nature. It expands on what second nature is limited by. It has the ability to mould data in new and unlike ways. And so, third nature is able to 'speed up, proliferate, divide, mutate, and beam in on u.s.a. from else where.[34] Information technology aims to create a balance between the boundaries of space and time (see second nature). This can be seen through the telegraph, information technology was the outset successful applied science that could send and receive data faster than a human existence could move an object.[35] Equally a result unlike vectors of people have the power to non only shape culture but create new possibilities that will ultimately shape society.

Therefore, through the use of second nature and 3rd nature guild is able to utilise and explore new vectors of possibility where information tin exist moulded to create new forms of interaction.[36]

Sociological uses [edit]

In sociology, informational gild refers to a postal service-modern type of lodge. Theoreticians similar Ulrich Beck, Anthony Giddens and Manuel Castells argue that since the 1970s a transformation from industrial club to advisory society has happened on a global scale.[38]

As steam ability was the technology continuing behind industrial society, so it is seen every bit the goad for the changes in piece of work arrangement, societal structure and politics occurring in the late 20th century.

In the volume Future Stupor, Alvin Toffler used the phrase super-industrial club to describe this type of order. Other writers and thinkers have used terms like "post-industrial society" and "post-modern industrial society" with a like meaning.

[edit]

A number of terms in electric current use emphasize related but unlike aspects of the emerging global economic order. The Information Society intends to be the most encompassing in that an economy is a subset of a society. The Information Historic period is somewhat limiting, in that information technology refers to a 30-year catamenia between the widespread employ of computers and the noesis economic system, rather than an emerging economic guild. The knowledge era is about the nature of the content, not the socioeconomic processes by which it will exist traded. The computer revolution, and cognition revolution refer to specific revolutionary transitions, rather than the end state towards which nosotros are evolving. The Data Revolution relates with the well known terms agricultural revolution and industrial revolution.

- The information economic system and the knowledge economy emphasize the content or intellectual property that is being traded through an information market or knowledge market place, respectively. Electronic commerce and electronic concern emphasize the nature of transactions and running a business, respectively, using the Internet and Globe-Wide Spider web. The digital economy focuses on trading bits in cyberspace rather than atoms in concrete space. The network economic system stresses that businesses will piece of work collectively in webs or equally part of business ecosystems rather than every bit stand-alone units. Social networking refers to the process of collaboration on massive, global scales. The internet economy focuses on the nature of markets that are enabled by the Internet.

- Knowledge services and knowledge value put content into an economic context. Knowledge services integrates Cognition management, within a Noesis arrangement, that trades in a Noesis market. In order for individuals to receive more than noesis, surveillance is used. This relates to the use of Drones as a tool in society to gather knowledge on other individuals. Although seemingly synonymous, each term conveys more than nuances or slightly dissimilar views of the aforementioned affair. Each term represents one attribute of the probable nature of economic activeness in the emerging post-industrial lodge. Alternatively, the new economic gild will incorporate all of the above plus other attributes that accept not yet fully emerged.

- In connection with the development of the information society, information pollution appeared, which in turn evolved information ecology – associated with information hygiene.[39]

Intellectual property considerations [edit]

One of the central paradoxes of the information society is that it makes information easily reproducible, leading to a multifariousness of liberty/control problems relating to intellectual property. Essentially, business organisation and capital letter, whose identify becomes that of producing and selling information and knowledge, seems to require command over this new resources then that it can finer exist managed and sold every bit the ground of the information economy. However, such command can evidence to exist both technically and socially problematic. Technically considering re-create protection is often easily circumvented and socially rejected considering the users and citizens of the information club can prove to be unwilling to accept such absolute commodification of the facts and data that compose their environs.

Responses to this concern range from the Digital Millennium Copyright Act in the United States (and similar legislation elsewhere) which make copy protection (see DRM) circumvention illegal, to the free software, open source and copyleft movements, which seek to encourage and disseminate the "liberty" of various data products (traditionally both as in "gratis" or free of cost, and liberty, equally in liberty to utilise, explore and share).

Caveat: Information society is often used by politicians meaning something like "nosotros all do internet at present"; the sociological term information society (or informational lodge) has some deeper implications about alter of societal structure. Because we lack political control of intellectual property, we are defective in a concrete map of issues, an analysis of costs and benefits, and functioning political groups that are unified by mutual interests representing different opinions of this diverse state of affairs that are prominent in the data society.[40]

Meet also [edit]

- Cyberspace

- Digitization

- Digital transformation

- Digital dark age

- Digital addict

- Digital phobic

- Data culture

- Information history

- Information industry

- Information revolution

- Internet culture

- Network social club

- Noogenesis

- Simon Buckingham and unorganisation

- Surveillance capitalism

- The Information Society (journal)

- World Summit on the Data Society (WSIS)

- Yoneji Masuda

References [edit]

- ^ Soll, Jacob, 1968- (2009). The data primary : Jean-Baptiste Colbert's secret state intelligence system. University of Michigan Press. ISBN978-0-472-02526-8. OCLC 643805520.

{{cite volume}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hilbert, M. (2015). Digital Technology and Social Change [Open Online Course at the University of California] freely available at: https://youtube.com/sentry?v=xR4sQ3f6tW8&list=PLtjBSCvWCU3rNm46D3R85efM0hrzjuAIg

- ^ Hilbert, K. (2015). Digital Engineering and Social Change [Open Online Course at the University of California] https://youtube.com/watch?5=KKGedDCKa68&list=PLtjBSCvWCU3rNm46D3R85efM0hrzjuAIg freely bachelor at: https://sail.instructure.com/courses/949415

- ^ Hilbert, M. (2015). Digital Engineering and Social Modify [Open Online Course at the University of California] freely available at: https://sheet.instructure.com/courses/949415

- ^ a b Beniger, James R. (1986). The Control Revolution: Technological and Economic Origins of the Information Order. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- ^ a b Webster, Frank (2002). Theories of the Data Lodge. Cambridge: Routledge.

- ^ Webster, F. (2006). Chapter ii: What is an data society? In Theories of the Information Guild, third ed. (pp. xv-31). New York: Routledge.

- ^ "Magic Lantern Empire: Reflections on Colonialism and Society", Magic Lantern Empire, Cornell University Printing, pp. 148–160, 2017-12-31, doi:10.7591/9780801468230-009, ISBN978-0-8014-6823-0

- ^ Buckland, Michael (March three, 2017). Information in Society. MIT Press.

- ^ James Boyle, 1996, vi[ vague ]

- ^ Kasiwulaya and Walter, Makerere University. Makerere Academy Press.[ vague ]

- ^ Buckland, Michael (2017). Information and Lodge. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. p. 22.

- ^ "Individuals using the Internet 2005 to 2014", Cardinal ICT indicators for developed and developing countries and the world (totals and penetration rates), International Telecommunication Union (ITU). Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ "Cyberspace users per 100 inhabitants 1997 to 2007", ICT Data and Statistics (IDS), International Telecommunication Union (ITU). Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ Hilbert, 1000.; Lopez, P. (2011-02-x). "The World's Technological Capacity to Shop, Communicate, and Compute Data". Science. 332 (6025): 60–65. Bibcode:2011Sci...332...60H. doi:x.1126/scientific discipline.1200970. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 21310967. S2CID 206531385.

- ^ a b c "The Globe's Technological Chapters to Store, Communicate, and Compute Information", Martin Hilbert and Priscila López (2011), Science, 332(6025), 60-65; complimentary access to the commodity through here: martinhilbert.internet/WorldInfoCapacity.html

- ^ a b "video animation on The Globe'south Technological Capacity to Shop, Communicate, and Compute Information from 1986 to 2010

- ^ Susan Crawford: "The Origin and Development of a Concept: The Information Society". Bull Med Libr Assoc. 71(4) October 1983: 380–385.

- ^ Rooney, Jim (2014). Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Intellectual Capital, Knowledge Management and Organizational Learning. Britain: Bookish Conferences and Publishing International Limited. p. 261. ISBN978-i-910309-71-1.

- ^ Machlup, Fritz (1962). The Product and Distribution of Noesis in the United States. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Peter Drucker (1969) The Age of Discontinuity. London: Heinemann

- ^ Marc Porat (1977) The Information Economic system. Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce

- ^ Karl Deutsch (1983) Soziale und politische Aspekte der Informationsgesellschaft. In: Philipp Sonntag (Ed.) (1983) Die Zukunft der Informationsgesellschaft. Frankfurt/Main: Haag & Herchen. pp. 68-88

- ^ Daniel Bell (1976) The Coming of Mail-Industrial Club. New York: Bones Books, 127, 348

- ^ Jean-François Lyotard (1984) The Postmodern Condition. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 5

- ^ Darin Barney (2003) The Network Society. Cambridge: Polity, 25sq

- ^ Peter Glotz (1999) Die beschleunigte Gesellschaft. Kulturkämpfe im digitalen Kapitalismus. München: Kindler.

- ^ Wolfgang Fritz Haug (2003) Loftier-Tech-Kapitalismus. Hamburg: Statement.

- ^ Nicholas Garnham (2004) Information Society Theory equally Ideology. In: Frank Webster (Ed.) (2004) The Information Society Reader. London: Routledge.

- ^ Wark 1997, p. 22.

- ^ Wark 1997, p. 23.

- ^ Wark 1997, p. 21.

- ^ Wark 1997, p. 24.

- ^ Wark 1997, p. 25.

- ^ Wark 1997, p. 26.

- ^ Wark 1997, p. 28.

- ^ "Welcome to E-stonia, the globe's most digitally avant-garde society". Wired . Retrieved fifteen July 2020.

- ^ Grinin, Fifty. 2007. Periodization of History: A theoretic-mathematical analysis. In: History & Mathematics. Moscow: KomKniga/URSS. P.x-38. ISBN 978-5-484-01001-i.

- ^ Eryomin A.L. Information ecology - a viewpoint// International Periodical of Environmental Studies. - 1998. - Vol. 54. - pp. 241-253.

- ^ Boyle, James. "A Politics of Intellectual Property: Environmentalism for the Net?" Duke Police force Journal, vol. 47, no. 1, 1997, pp. 87–116. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1372861.

Works cited [edit]

- Wark, McKenzie (1997). The Virtual Commonwealth. Allen & Unwin, St Leonards.

Further reading [edit]

- Alan Mckenna (2011) A Human being Correct to Participate in the Information Society. New York: Hampton Printing. ISBN 978-1-61289-046-iii.

- Lev Manovich (2009) How to Represent Data Society?, Miltos Manetas, Paintings from Contemporary Life, Johan & Levi Editore, Milan . Online: [1]

- Manuel Castells (2000) The Rise of the Network Society. The Information Historic period: Economic system, Society and Civilization. Volume i. Malden: Blackwell. Second Edition.

- Michael Dawson/John Bellamy Foster (1998) Virtual Capitalism. In: Robert W. McChesney/Ellen Meiksins Forest/John Bellamy Foster (Eds.) (1998) Capitalism and the Information Age. New York: Monthly Review Press. pp. 51–67.

- Aleksander Aristovnik (2014) Evolution of the data social club and its bear on on the education sector in the EU : efficiency at the regional (Basics two) level. In: Turkish online periodical of educational technology. Vol. 13. No. 2. pp. 54–60.

- Alistair Duff (2000) Information Society Studies. London: Routledge.

- Esther Dyson/George Gilder/George Keyworth/Alvin Toffler (1994) Cyberspace and the American Dream: A Magna Carta for the Cognition Age. In: Future Insight 1.2. The Progress & Freedom Foundation.

- Tony Fitzpatrick (2002) Critical Theory, Information Society and Surveillance Technologies. In: Information, Communication and Society. Vol. 5. No. three. pp. 357–378.

- Vilém Flusser (2013) Post-History, Univocal Publishing, Minneapolis ISBN 9781937561093 [ii]

- Christian Fuchs (2008) Internet and Guild: Social Theory in the Information Age. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-96132-7.

- Christian Fuchs (2007) Transnational Space and the 'Network Club'. In: 21st Century Social club. Vol. 2. No. 1. pp. 49–78.

- Christian Fuchs (2005) Emanzipation! Technik und Politik bei Herbert Marcuse. Aachen: Shaker.

- Christian Fuchs (2004) The Antagonistic Cocky-Arrangement of Modern Social club. In: Studies in Political Economic system, No. 73 (2004), pp. 183– 209.

- Michael Hardt/Antonio Negri (2005) Multitude. State of war and Democracy in the Historic period of the Empire. New York: Hamish Hamilton.

- Michael Hardt/Antonio Negri Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- David Harvey (1989) The Condition of Postmodernity. London: Blackwell.

- Fritz Machlup (1962) The Production and Distribution of Knowledge in the United States. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- OECD (1986) Trends in The Information Economy. Paris: OECD.

- OECD (1981) Information Activities, Electronics and Telecommunications Technologies: Impact on Employment, Growth and Trade. Paris: OECD.

- Pasquinelli, M. (2014) Italian Operaismo and the Information Automobile, Theory, Culture & Gild, beginning published on February two, 2014.

- Pastore M. (2009) Verso la società della conoscenza, Le Lettere, Firenze.

- Peter Otto/Philipp Sonntag (1985) Wege in dice Informationsgesellschaft. München. dtv.

- Pinterič, Uroš (2015): Spregledane pasti informacijske družbe. Fakulteta za organizacijske študije v Novem mestu ISBN 978-961-6974-07-three

- Radovan Richta (1977) The Scientific and Technological Revolution and the Prospects of Social Development. In: Ralf Dahrendorf (Ed.) (1977) Scientific-Technological Revolution. Social Aspects. London: Sage. pp. 25–72.

- Dan Schiller (2000) Digital Capitalism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Rudi Schmiede (2006a) Noesis, Work and Bailiwick in Informational Capitalism. In: Berleur, Jacques/Nurminen, Markku I./Impagliazzo, John (Eds.) (2006) Social Informatics: An Information Gild for All? New York: Springer. pp. 333–354.

- Rudi Schmiede (2006b) Wissen und Arbeit im "Informational Capitalism". In: Baukrowitz, Andrea et al. (Eds.) (2006) Informatisierung der Arbeit – Gesellschaft im Umbruch. Berlin: Edition Sigma. pp. 455–488.

- Seely Brown, John; Duguid, Paul (2000). The Social Life of Information. Harvard Business School Press.

- Nico Stehr (1994) Arbeit, Eigentum und Wissen. Frankfurt/Chief: Suhrkamp.

- Nico Stehr (2002a) A World Made of Cognition. Lecture at the Conference "New Cognition and New Consciousness in the Era of the Knowledge Society", Budapest, Jan 31, 2002. Online: [3]

- Nico Stehr (2002b) Knowledge & Economic Conduct. Toronto: Academy of Toronto Press.

- Alain Touraine (1988) Return of the Actor. Minneapolis. Academy of Minnesota Printing.

- Jan Van Dijk (2006) The Network Society. London: Sage. 2nd Edition.

- Yannis Veneris (1984) The Informational Revolution, Cybernetics and Urban Modelling, PhD Thesis, Academy of Newcastle upon Tyne, Uk.

- Yannis Veneris (1990) Modeling the transition from the Industrial to the Informational Revolution, Surroundings and Planning A 22(three):399-416. [four]

- Frank Webster (2002a) The Information Society Revisited. In: Lievrouw, Leah A./Livingstone, Sonia (Eds.) (2002) Handbook of New Media. London: Sage. pp. 255–266.

- Frank Webster (2002b) Theories of the Information Society. London: Routledge.

- Frank Webster (2006) Theories of the Data Club. third edition. London: Routledge

- Gelbstein, E. (2006) Crossing the Executive Digital Divide. ISBN 99932-53-17-0

External links [edit]

- Special Report - "Information Society: The Next Steps"

- Knowledge Cess Methodology - interactive country-level data for the information society and noesis economy

- The origin and development of a concept: the information society.

- Global Information Gild Project at the World Policy Institute

- UNESCO - Observatory on the Information Society

- I/Due south: A Journal of Law and Policy for the Data Society - Ohio State law journal which addresses legal aspects related to the data society.

- [five] - Participation in the Broadband Society. European network on social and technical research on the emerging information society.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Information_society

0 Response to "Knowing What Has Gone on and Is Going on Around You in Society Is Called"

Post a Comment